As part of my dissertation, I researched literacy levels in Kinross-shire from 1696 until 1872 when the 1872 Education (Scotland) Act was introduced. This blog forms part of my dissertation explaining the evolution of education in Kinross-shire which is reflection of the rest of the nation.

Currently part of Perth and Kinross region, Kinross-shire is Scotland’s second smallest county. It is dominated by a six-kilometre fresh water loch called Loch Leven which has a number of small islands including St Serf Island.

Once the county capital, Kinross was a staging post on the old Great North Road half way between North Queensferry and Perth. Over the centuries, it shared jurisdiction with other administrative areas including Clackmannanshire, Fife, Tayside and Perthshire. Today, the parishes include Cleish, Kinross, Orwell, Portmoak and Tullibole.

Kinross-shire has had a long history of education, which can be traced back to the eighth century when monks occupied the area. On St Serf Island, a priory was established in the eighth century by the ‘Kele Dei’ later known as the Culdees under Brude V, the last King of the Picts. During their four-hundred-year occupation, the island became a centre of literacy.

When Bishop Robert of St Andrews of the Augustinian community granted a charter in around 1152, a list of all sixteen books belonging to the Culdees was included. These were religious works and would have been valuable particularly when a hand-written copy of the Bible cost as much as building a church.1

Around 1420, Andrew de Wyntoun, Prior of St Serf and later Canon of St Andrews, wrote the Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland apparently on the island.2 It is a compilation of stories from older records of Scottish history including Macbeth’s three witches.

By 1560, John Knox and a small group of clergymen set out guidelines for spiritual reform in the First Book of Discipline encouraging every parish to have a school providing ‘…virtuous education and godly upbringing of the youth of this Realm’.3 Their guidelines created an opportunity for children to progress in education and from an early stage had set in motion the Scottish educational movement, which could be seen to have evolved into the current Curriculum for Excellence.

By 1696 the ‘Act for Settling of Schools’ was passed by Scottish Parliament requiring every parish to have a school. Kinross already had several schoolmasters by the time the act was implemented.4 This was also around the time when the emergence of the Scottish Enlightenment saw advances in printing, making books less rare and more affordable.

With good road links, Kinross-shire was well situated to encourage book sellers to trade. John Watson, Kinross bookseller from 1733 until 1739, sold copies of Reverend Ebenezer Erskine’s sermons.5 Erskine was a local minister who had protested against the General Assembly’s legislation on patronage believing that it was the parishioners’ right to elect their minister. Rebuked and suspended, Erskine and three other ministers formed themselves into an alternative congregation, the Secession Church, in 1733 in Gairney Bridge, one mile south of Kinross. This was the forerunner of the Free Church, a movement, which later spread across Scotland.

The combination of industrialisation, immigration and an increase in urban population was putting pressures on the provision of education. Such pressures threatened the parochial school system particularly after the disruption in 1843 when many parish schoolmasters left to join the Free Church movement.

After this period, Scotland, including Kinross-shire, saw an increasing emergence of non-conformist churches and schools. All these pressures led to the introduction of the 1872 Education (Scotland) Act when control by the church was taken away creating a non-sectarian system of largely free public schools managed by school boards.6

1 Cosmo Innes, Scotland in the Middle Ages’, Edinburgh, 1860, p.333.

2 Mackay, A History of Fife and Kinross, p.352.

3 www.swrb.com/newslett/actualNLs/bod_ch00.htm

4 John Durkan, Scottish Schools and Schoolmasters 1560-1633, Cornwall, 2013, p.324.

5 Scottish Book Trade Index, https://data.cerl.org/sbti/007817

6 This was not the case for Roman Catholic and Episcopalian schools.

You may also like...

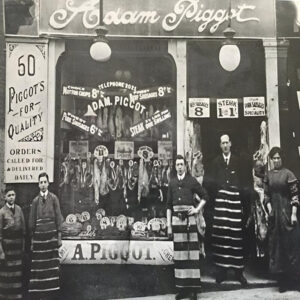

Butcher Family History: My Ancestor Was a Butcher

Learn about your butcher family history and find out what life was like for butchers in Scotland’s towns and villages.

The Balfour Surname – Meaning and History

The Balfour surname is Scottish, found in Orkney, Aberdeen-shire, Angus and Fife. It is a place-name meaning “farm by the pasture.”

Unlocking Family Tree Secrets

A family tree was brought to life by an old suitcase revealing links to Balvaird Castle, Murrayshall and Scone Palace.