Are you trying to trace an old watchmaker from your family tree? Following my last post on ‘My Ancestor was a…’ weaver, this month I am exploring the old occupation of the watchmaker. In this post, I will help you trace your old watchmaker. Additionally, I will explore the intriguing history of timekeeping and mention a few famous Scottish watchmakers.

Background to time keeping in Scotland

Until the arrival of the railways, people mostly did not pay attention to seconds, minutes, and hours. After all, agricultural labourers rose at dawn and went to bed at sunset.

Early references to timekeeping in Scotland tended to be linked with the parish church that used bells to summon the parishioners on Sundays. Bells were also used to celebrate events or ring out a warning to parishioners.

It was not until the 19th century when trains travelled across the country according to timetables that timekeeping became vital.

Watchmaking was, and still is, a highly skilled craft. Many needle-makers and jewellers took up the craft and made their own tools and timepieces. They needed to have a good understanding of artistic design and mechanics. In addition, they needed good eyesight and often used special magnifiers such as a ‘loop’, a small magnifying glass worn in the eye socket.

Portable timepieces, or watches, were made available in Britain from the late 16th century. Anyone who owned a watch was either very wealthy, important, or both. Interestingly these timepieces normally had just one hour hand. Minute hands only began to appear in the late 18th century and early 19th century.

How did my ancestor become a watchmaker?

Anyone wanting to be a watchmaker needed to go through a seven-year apprenticeship, often starting at the age of 14. Apprenticeships usually fell under the jurisdiction of the Incorporation of Hammermen. This organisation can be found in many Scottish towns and it was a very influential trade association. It included gold and silversmiths, locksmiths, blacksmiths, cutlers, saddlers, armourers, pewterers, and, from the 17th century onwards, watch and clockmakers. After completing their apprenticeship, they could apply to the incorporation by paying a fee and submitting a sample of their work.

Generally, individuals had distinct and specialised skills. For example, one person might be an expert in ceramic dial painting, while another might make outstanding hinges. Some had talents that lay in crafting watch pendants while others were highly skilled in creating beautifully adorned watch cases. So, do you have an old watchmaker in your ancestry? or perhaps you have inherited an old watch?

A watchmaker, as well as a clockmaker, was seen as a master of their trade. Owning one of their timepieces was a symbol of status, something only the rich, nobles, and powerful people could afford.

How do I trace my old watchmaker ancestor?

Official records

- Census returns can help give clues as to when your ancestor worked as a clock or watchmaker.

- In 1797 the unpopular Clock & Watch Tax was imposed on owners of watches and clocks. It nearly ruined the country. Thousands of watch and clockmakers became unemployed and the tax was appealed the following year. Two volumes of the original tax rolls for 19 Scottish counties survive. If your ancestor is listed you can discover how many watches and clocks they owned and how much duty was paid on ScotlandsPlaces. This website also provides the old occupations for residents who paid taxes.

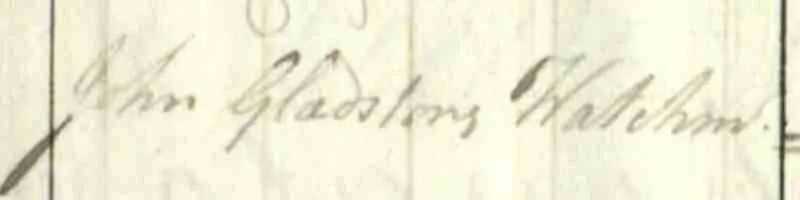

John Glastons, old watchmaker from Biggar (Clock & Watch Tax Toll 1797-1799 E326/12/2/151 - Valuation Rolls on the ScotlandsPeople website will also list the old occupation where your ancestor resided.

Old watchmakers from the 1855 Edinburgh Valuation Roll

Directories

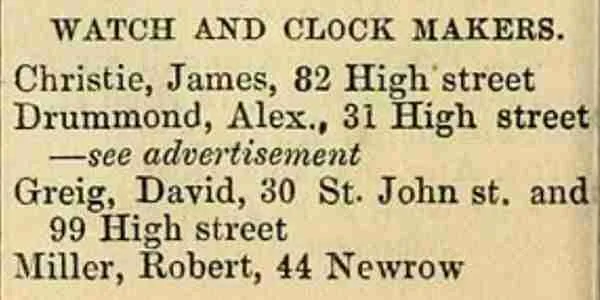

- Check post office directories to find out if your ancestor had a business in the area. In Scotland, you can look up the Scottish Post Office Directories on the National Library of Scotland website or go to your local library.

1862 Perth Post Office Directory, page 222

Wills and obituaries

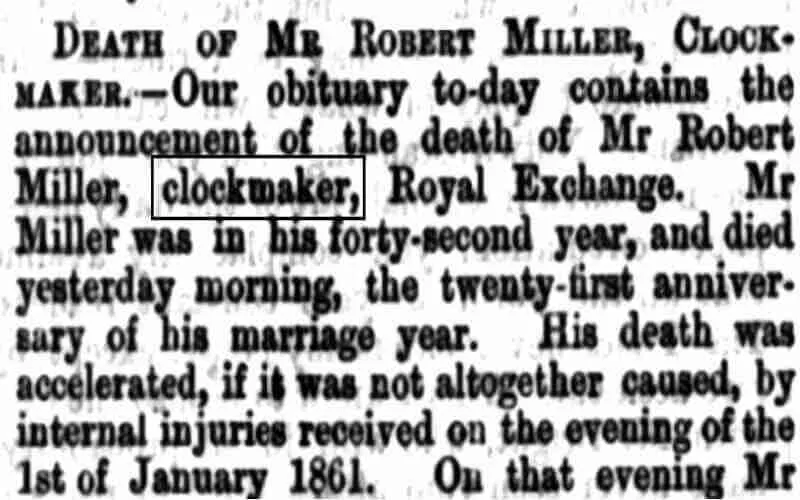

- Obituaries can provide a huge amount of detail regarding a person’s working life so try to find local newspaper family notices on websites such as British Newspaper Archives or FindmyPast.

Edinburgh Daily Review 14 December 1863

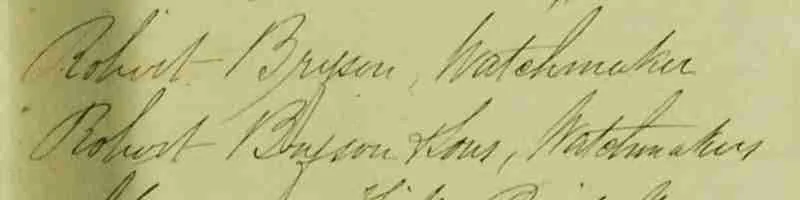

- Wills can supply new information about the occupation and whether the trade was a family tradition. Therefore, look up the legal documents on the ScotlandsPeople website.

- Gravestones can identify clock makers such as the one of Thomas Reid (1746 – 18131) from Edinburgh. Read my post on Burial Records in Scotland to find out more about locating a grave.

Gravestone of Thomas Reid (1746-1831) at Calton Cemetery

Other resources to trace old watchmakers

- Local archives and the National Records of Scotland will have records about clock and watchmakers. So, check out their online databases by googling the local archive and online catalogue.

- Look at the family tree sections on subscription genealogical websites to make contact with possible relatives and you may be able to share information to further your own research. You can also post inquiries on the message boards and mailing lists.

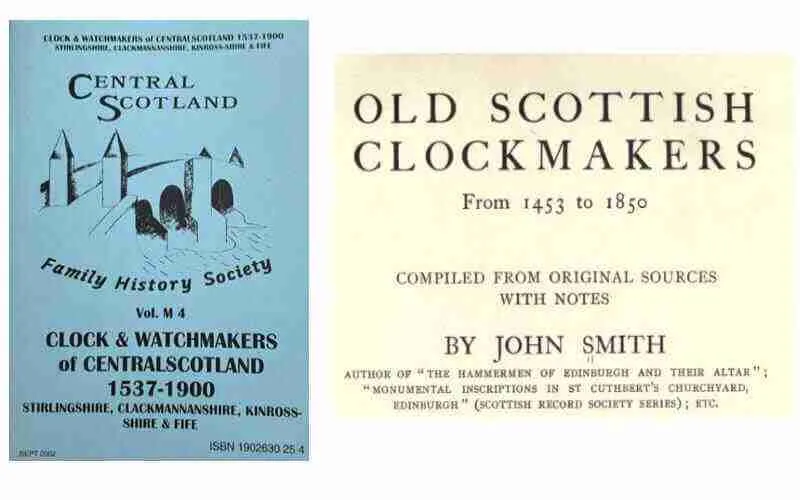

- Publications about watch and clockmakers. There are books available such as the Clock & Watchmakers of Central Scotland 1537 – 1900’ published by Donald Whyte. There is also ‘Old Scottish Clockmakers from 1453 to 1850’ by John Smith that can be found on archive.org.

- The British Watch and Clock Makers Guild, established in 1907, might have useful information or links to other horological institutions’ websites and relevant publications.

Some famous old watchmakers in Scotland

While Scotland has not been as historically renowned for watchmaking as some other countries, there have been notable Scottish watchmakers. One example is Alexander Cumming (1733-1814) who was born in Edinburgh. He was credited for inventing the siphon escapement, an important component in the accuracy of timekeeping in clocks and watches. An inventor, he was also the first person to patent a design of the flushing toilet!!

In addition, Thomas Reid (1746 – 1831) was a Scottish watchmaker who was recognised for his high-quality watches, clocks and chronometers.

The history of time keeping

The history of timekeeping reflects a continuous quest for accuracy and precision, from ancient sundials to modern atomic clocks. Each innovation contributed to our ability to measure time with increasing precision and portability.

1500 BC – 14th Century

- Ancient Sundials (1500 BC): One of the earliest methods of timekeeping involved sundials. Ancient civilizations, including the Egyptians and Greeks, used sundials to measure the passage of time based on the position of the sun’s shadow.

- Water Clocks (1400 BC): Water clocks, or ‘clepsydrae’, were used in ancient cultures like the Babylonians and Chinese. These devices measured time-based on the flow of water from one container to another. It inspired various timekeeping mechanisms, including the hourglass.

- The Hourglass became more prevalent during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, gaining popularity as a maritime tool for navigation. Its simple design made it suitable for a range of timing purposes, from measuring shorter intervals to regulating longer tasks.

- Ancient Mechanical Clocks (14th Century): Mechanical clocks with gears and weights emerged in medieval Europe. These early clocks, found in churches and public spaces, marked the hours audibly with bells.

- The Candela Horaria was a candle marked at regular intervals. As the candle burned down, each marking indicated the passing of time, often by the hour.

15th – 19th centuries

- Spring-Driven Clocks (15th Century): The development of spring-driven clocks in the 15th century marked a significant advancement. These clocks replaced weights with coiled springs, enabling more portable timepieces.

- Pendulum Clocks (17th Century): In 1656, Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens invented the pendulum clock, greatly improving accuracy. The pendulum’s regular motion allowed for more precise timekeeping.

- Pocket Watches (16th Century): The 16th century saw the emergence of portable timepieces known as pocket watches. They became popular accessories, particularly among the upper class.

- John Harrison and Marine Chronometer (18th Century): English clockmaker John Harrison developed the marine chronometer, a highly accurate timekeeping device. It revolutionized navigation by providing precise time at sea.

20th – 21st centuries

- Quartz Crystal Clocks (1920s): The discovery of the piezoelectric properties of quartz crystals led to the development of quartz clocks. The regular vibration of quartz crystals provided remarkable accuracy.

- Atomic Clocks (20th Century): The atomic clock, based on the vibrations of atoms, became the most accurate timekeeping device. The definition of the second was refined based on atomic vibrations, leading to the development of International Atomic Time (TAI).

- Global Timekeeping Standards (1970s): Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) was established as an international time standard, incorporating atomic time with occasional leap seconds to account for Earth’s irregular rotation.

- Precision Timekeeping in the Digital Age: In the 21st century, atomic clocks continue to play a crucial role in technologies like GPS, ensuring precise timekeeping globally.

In summary…

watchmakers from the 18th and 19th century Scotland were master craftsmen who contributed to both the functional and aesthetic aspects of timekeeping. Their work reflected the technological advancements and artistic sensibilities of the period, leaving a lasting legacy in the form of beautiful, crafted timepieces.

Thank you for joining me on this historical journey about old watchmakers. I hope you enjoyed reading my post and if you want me to write about an old occupation, then let me know below in the comments.

Good luck with your research.

Until my next post, haste ye back.

You may also like...

Butcher Family History: My Ancestor Was a Butcher

Learn about your butcher family history and find out what life was like for butchers in Scotland’s towns and villages.

The Balfour Surname – Meaning and History

The Balfour surname is Scottish, found in Orkney, Aberdeen-shire, Angus and Fife. It is a place-name meaning “farm by the pasture.”

Unlocking Family Tree Secrets

A family tree was brought to life by an old suitcase revealing links to Balvaird Castle, Murrayshall and Scone Palace.

Edinburgh Daily Review 14 December 1863

Edinburgh Daily Review 14 December 1863